Infrared Remote Controls: The Process

Pushing a button on a remote control sets in motion a series of events that causes the controlled device to carry out a command. The process works something like this:

- You push the "volume up"buttonon your remote control, causing it to touch thecontactbeneath it and complete the "volume up" circuit on the circuit board. The integrated circuit detects this.

- Theintegrated circuitsends the binary "volume up" command to the LED at the front of the remote.

- TheLEDsends out a series of light pulses that corresponds to the binary "volume up" command.

One example of remote-control codes is the Sony Control-S protocol, which is used for Sony TVs and includes the following 7-bit binary commands (source:ARRLWeb):

Advertisement

Button 1 = 000 0000

Button 2 = 000 0001

按钮3 = 000 0010

Button 4 = 000 0011

Channel Up = 001 0001

Channel Down = 001 0001

Power On = 001 0101

Power Off = 010 1111

Volume Up = 001 0010

Volume Down = 001 0011

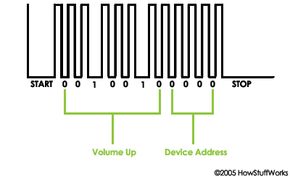

The remote signal includes more than the command for "volume up," though. It carries several chunks of information to the receiving device, including:

- “开始”命令

- the command code for "volume up"

- the device address (so the TV knows the data is intended for it)

- a "stop" command (triggered when you release the "volume up" button)

So when you press the "volume up" button on a Sony TV remote, it sends out a series of pulses that looks something like this:

When the infrared receiver on the TV picks up the signal from the remote and verifies from the address code that it's supposed to carry out this command, it converts the light pulses back into the electrical signal for 001 0010. It then passes this signal to the microprocessor, which goes about increasing the volume. The "stop" command tells the microprocessor it can stop increasing the volume.

Infrared remote controls work well enough to have stuck around for 25 years, but they do have some limitations related to the nature of infrared light. First, infrared remotes have a range of only about30 feet(10 meters), and they requireline-of-sight. This means the infrared signal won't transmit through walls or around corners -- you need a straight line to the device you're trying to control. Also, infrared light is so ubiquitous thatinterferencecan be a problem with IR remotes. Just a few everyday infrared-light sources includesunlight,fluorescent bulbsand the human body. To avoid interference caused by other sources of infrared light, the infrared receiver on a TV only responds to a particular wavelength of infrared light, usually 980 nanometers. There are filters on the receiver that block out light at other wavelengths. Still, sunlight can confuse the receiver because it contains infrared light at the 980-nm wavelength. To address this issue, the light from an IR remote control is typically modulated to a frequency not present in sunlight, and the receiver only responds to 980-nm light modulated to that frequency. The system doesn't work perfectly, but it does cut down a great deal on interference.

While infrared remotes are the dominant technology in home-theater applications, there are other niche-specific remotes that work on radio waves instead of light waves. If you have a garage-door opener, for instance, you have an RF remote.