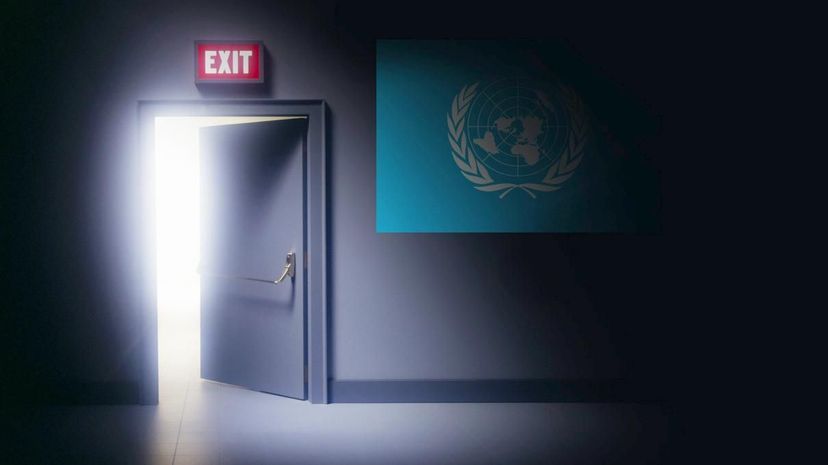

On Jan. 3, U.S. Rep. Mike Rogers, a Republican from Alabama, had barely been sworn into office for a new term when he and seven co-sponsors introduced theAmerican Sovereignty Restoration Act of 2017. If Congress were to pass the bill and sign it into law, the United States would be compelled to terminate its membership in the United Nations and all organizations connected to the international body — and stop providing funding to them, as well.

The U.S. is scheduled to be the biggest single contributor to the U.N.'s2017 general budget, paying $611 million of the $2.58 billion total, and covering 29 percent of the U.N.'s $7.87 billion peacekeeping budget for the 2016-2017 fiscal year, which adds another $1.94 billion to the tab.

Advertisement

Rogers' office in Washington didn't respond to an emailed request for more information. But in apress releaseon his website, the Congressman charged that the international organization had "attempted a number of actions which aimed to encroach on the rights granted to U.S. citizens under our Constitution," though without specifying what those actions were. He also called the 72-year-old organization "a waste of taxpayer dollars."

Similar legislation was introduced in 2013and 2015, and got nowhere. They were outgrowths of the original American Sovereignty Restoration Act movement spearheaded by libertarian icon Ron Paul, who introduced measures for a U.N. exit every year from 1997 through 2011. But Rogers and the bill's other backers may be drawing encouragement this time around from new President Donald J. Trump's dim view of the U.N., which he derided in aDecember tweet. "The United Nations has such great potential but right now it is just a club for people to get together, talk and have a good time," Trump said. Since then, the Trump administration has proposedcutting voluntary U.S. support for the U.N. and other international organizations by 40 percent.

If Rogers' bill did somehow pass both houses of Congress, and Trump signed it into law, what would happen then? How would the U.S. actually go about quitting the U.N.? Is there even an official process for leaving?

The U.N. itself is keeping mum about the subject. "We would not speculate about legislation which is still part of a domestic legislative process," says Farhan Haq, deputy spokesperson for U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, via email. "Since most of your questions are based on the hypothetical possibility that the legislation passes, I don't really have anything to say."

One problem is that there's only one example in U.N. history of a country deciding to abandon its membership — Indonesia — and it only stayed away for a brief time.

Lessons From the Past

According to U.N. historiansAndrew W. Cordier and Max Harrelson, the story began in late 1964, when Indonesian president Sukarno proclaimed publicly that his country would quit the U.N. if the Federation of Malaysia were seated as a member of the U.N. Security Council. The Indonesian leader, a vehement anti-colonialist, was irked that Malaysia was a member of theBritish Commonwealth.

Gregory Fealy, an associate professor at Australian National University and an expert in Asian history and Indonesian politics, says that Sukarno not only viewed the Malay peninsula as a veritable knife pointing into Indonesia's belly, but that he had come to see the U.N. itself as a just another defender of European colonialism. The Indonesian leader talked of shifting away from the West and aligning Indonesia with the Soviet Union, North Vietnam and other communist nations. He even floated the idea of creating a sort ofalternative to the U.N., called the Conference of Newly Emerging Forces.

But a lot of that may just have been bluster, says Fealy. "Behind all this international activism was the domestic reality that Sukarno's political position and the nation's economy were increasingly perilous," he says. "Many have argued that Sukarno used the Malaysia issue to distract attention from internal problems."

According to Cordier's and Harrelson's account, newly installed U.N. Secretary-General U Thant reached out personally to Sukarno, but the line in the sand already had been drawn, and Thant wouldn't give in to the ultimatum. Thus, in January 1965, a letter from Indonesian Deputy Prime Minister Roden Subandrio notified the U.N. that Indonesia was quitting the international body.

Thant pondered what to do, and took nearly two months to respond. While Article 6 of theU.N. Charter给了大会踢出的力量member that didn't follow the rules, there was actually nothing in the document about how a country could voluntarily leave. After consulting with U.N. delegates and his own legal staff, Thant ultimately concluded that there was nothing he could do to prevent a member state from quitting. So he told Subandrio that he regretted Indonesia's decision. "The withdrawal was accepted without any official acknowledgement from either the Security Council or the General Assembly," Cordier and Harrelson wrote.

Rejoining the Club

Thant was careful to let Indonesia know it was welcome to come back anytime. In his introduction to the U.N.'s annual report in September 1965, Thant wrote that he hoped that the country's withdrawal was "only a temporary phase," and that it would decide that its long-term interests "can best be served by resuming its membership and by participating fully in the Organization's constructive activities."

As it turned out, that happened pretty quickly. After Sukarno was overthrown in a 1966 military coup, new leader Gen. Suharto, even before he consolidated power, decided to rejoin the U.N. as a sign that Indonesia again would cooperate with the West, according to Fealy. The country was quietly welcomed back into the fold in September 1966, and no nation since then has left, or tried to leave, the international organization.

Advertisement