If you watch cable news these days, you may have heard a lot of impassioned debate about a phenomenon that some call family reunification and others call chain migration, in whichimmigrantswho settle in the U.S. then sponsor family members to enter the country and join them.

“在当前破碎系统,单个immigrant can bring in virtually unlimited numbers of distant relatives," President Donald J. Trump complained in his 2018 State of the Union address. To fix that perceived problem, Trump favors passage of the RAISE Act, a piece of legislation that, if enacted, would reduce the ability of Americans to sponsor extended family and adult family members, and would impose a skills-based point system for deciding who gets to enter the U.S. As a result, the act would cut legal immigration to the U.S. by a projected 41 percent in its first year alone.

Advertisement

From the tenor of the discussion, you might think that it's pretty easy to obtain a“绿卡”, the permit that enables a foreign national to live and work in the U.S. permanently, provided that you've got relatives here already. But try telling that to a naturalized citizen from, say, the Philippines, who's been trying to bring a brother or sister here to live. Under current U.S. immigration regulations, that would-be immigrant sibling most likely faces a pretty long wait. According to the U.S. Department of State's latestVisa Bulletin,(currently covering May 2018) siblings are now eligible for processing via family reunification if they filed immigration paperwork before Feb. 1, 1995.

You read that right. Feb. 1, 1995. That means the projected wait time, for a brother or sister who applies today, would be more than 23 years. Other categories of family members from various countries face similarly long waits. A sibling from Mexico faces a projected wait of slightly more than 20 years, while one from India probably will have to sit tight for about 14 years. And those projections aren't set in stone. The wait could get shorter or longer, depending on other factors.

"People think you just apply, you get in line and you come,"Joshua Breisblattexplained in a telephone interview. He's an attorney and senior policy analyst at theAmerican Immigration Council, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that supports immigration. "It's much more complicated than that, with all the categories and the limits."

U.S. immigration regulations tend toward the inscrutable, in part because it essentially has multiple systems (the council has a nine-page document to explain it): One that's family-based; another based upon employment; and separate routes for refugees and those seeing asylum. There are numerical limits on categories of immigrants and countries as well. But let's focus upon family-based and employment-based, which Breisblatt says are the two main categories, accounting for most of the people who enter the U.S. legally and become permanent residents.

There are four categories of family-based immigration:

- F1: Unmarried sons and daughters over age 21 of U.S. citizens

- F2A: Spouses and children of permanent residents

- F2B: Unmarried sons and daughters over age 21 of permanent residents

- F3: Married sons and daughters of U.S. citizens

- F4: Brothers and sisters of adult U.S. citizens

The family-based portion of the system has a theoretical ceiling of 480,000 immigrants allowed into the country each year, though according to Breisblatt the actual number often is higher. That's because the F2A category of immigration preferences — and minor children of permanent U.S. residents — isn't capped. But that doesn't mean they get in right away. Those applications can face a projected wait time of nearly two years, according to the latest State Department bulletin.

Other family categories have caps on the number of people who can use them. For brothers and sisters, for example, the cap is 65,000 immigrants per year, unless there happens to be unneeded visas from the first three categories to supplement.

In addition to the cap on categories, there's also a rule that no country can exceed 7 percent of the total people emigrating to the U.S. in a given year.

"China, India, Mexico and the Philippines are countries where there's a high desire to emigrate," Briesblatt explains. "They have longer wait times because they hit the limit sooner."

OK, so forget about the family connection. What about a foreign national without relatives in the country, who wants to come here to take a job? While that's often a quicker route, in some cases, those immigrants have to wait for years, as well.

Immigration for employment purposes is capped at a much lower level, just 140,000 people per year. But the number of available slots actually is less, because immigrants are allowed to bring spouses and minor children, and those both are counted against the 140,000 limit, according to Briesblatt.

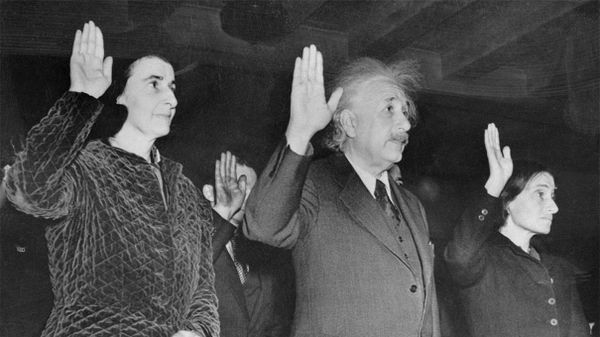

Additionally, not all workers are equal. There are differentemployment-based preference categories.The first preference, EB-1, AKA the "Einstein Visa," goes to people deemed to have extraordinary ability in various fields. There also are categories for people with advanced degrees, professionals and skilled workers, and another for investors willing to put up $1 million or more to underwrite a new business that would employ at least 10 full-time workers. ($500,000 is enough if the investment is targeted at a rural or high-unemployment area, as this2014 CityLab articlenotes.)

To make things even more complicated, the 7 percent limit on immigration from a particular country still has to be factored in. As a result, some workers from China could face a projected wait of 11 years, while an immigrant from Vietnam in the same category might be eligible immediately for a Green Card.

Advertisement